The images are compelling in this old Australian video, which I showed to elementary school teachers a few years ago. I see them still: the adult dropping a cigarette, yelling at a driver, berating a racialized worker, brushing past a person on the stairs, not stopping to help with dropped shopping. In each scene the adult acts, and the child’s behaviour is a perfect copy. In the final scene, the man yells, with threatening fist, and violent words thrown at the cowering woman, and the child yells and threatens too, in exact ugly emphasis.

One of the teachers couldn’t stop her tears, “that’s what home is like for so many of my kids” she said. But my exercise had been intended to shift perspectives for the teachers. I wanted to get them thinking about what those children were being taught at home, what they were learning well from life. I had hoped to use this video as a catalyst to move teachers from focussing on the horrors of their students’ homes, or thinking of these students as behaving badly in school, to the lessons they were learning out of school.

This shift of thinking seemed surprisingly hard, like exercising a new muscle, but the next step seemed a little easier. I suggested we think about that learning that was happening at home as like drinking poison, and our next task was to think of possible antidotes they could provide at school. I wanted the teachers to avoid losing energy in despair, in feeling helpless to change their students’ home lives, but instead to find a place from which to act, to see that they might be able to make a difference in these students’ lives even when students remained in those disturbing homes.

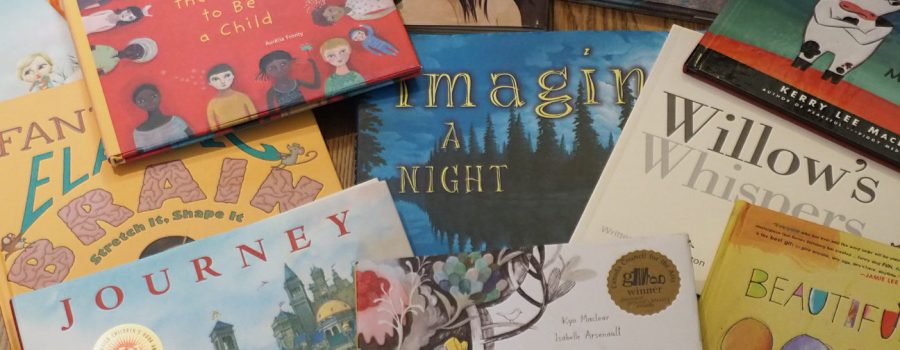

So we brainstormed what students could be learning in harsh homes. We recognized lessons about the pain of cruelty, about disregard and disrespect for another’s needs, about yelling and cursing and failed communication, about threat and fear, and the danger of making mistakes. Then we focused on the antidote to that poisonous brew, spending an afternoon with a glorious array of children’s books, courtesy of a wonderful local bookstore*. We had books that offered different examples of homes and ways of living, lives of violence and peace, of fantasy and stark reality.

These brightly coloured books drew us all in to excitement of possibility. Although many of the books showed lives in difficult situations: living with angry parents, or those with addictions or mental health struggles, and the impacts of fighting, others showed realities of escaping to shelters, adjusting to foster homes, living with grannies, aunties and others. They showed a wide variety of children living in different conditions, in different countries. For how else can children learn that they are not alone in their difficult experience, and that their family constellation is not the only way they might live?

We included beautiful books that introduced children’s rights, and books that made it clear that making mistakes can lead to new creative beauty, there were stories of bullying and mistreatment, and community and engagement in supporting others, in how to respond to injustice and change the picture. Books that supported understanding emotions, ones that helped students learn about how and where they feel an emotion in their body, and ones that revealed how emotions might be released safely, were all part of the eclectic mix spread out in the room sparking energetic conversation.

We talked a lot about ways the teachers might introduce these books and the range of ideas they contained, not just as passive resources in the classroom, or library, but also woven into the curriculum. We were animated as we imagined a myriad of other active ways of creating a culture of kindness in the classroom, of developing good communication skills. We looked at how to grow gentleness with mistakes, and errors, and cultivate communities rich with compassion and care and appreciation for every unique way of coping with the conditions of our lives.

That day those teachers bought many books for their schools and were energized by the work the they could do in their classroom. When we frame this curriculum as an antidote to what is learned in violent homes, then it seems it holds more power to reduce despair, gains a higher priority in the never-ending demands on teachers, and classroom time, and can become a key part of the culture of the organization or institution, growing more power for change.

As I remember that exciting work with elementary teachers I think about how the idea of teaching an antidote to the poison of violence might apply in other settings. Are you involved in an educational or community setting? Do you offer an antidote to violence? If so, what does that look like concretely for you, and what differences have you seen?

*Many thanks to Sheila Koffman, much missed founder of Another Story Books, on Roncesvalles, in Toronto, who was generous enough to support this important work with her staff time and bookstore resources, and trust that we would use her books with care.

And to Kelly Hayes and Carol Zavitz from ETFO, the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario, for having the vision to initiate a 6 day training to support their teachers to work with students affected by violence: Too Scared to Learn.

Note: I am tempted to offer book lists—I have developed many—but as new books are published so frequently and every age range will need different materials, instead I want to send you to Another Story Books in person or online for their knowledge and up-to-date information.

Leave a Reply

We want to hear from you